2021

Opening Film

Festival Spotlight

Fantastic Beats

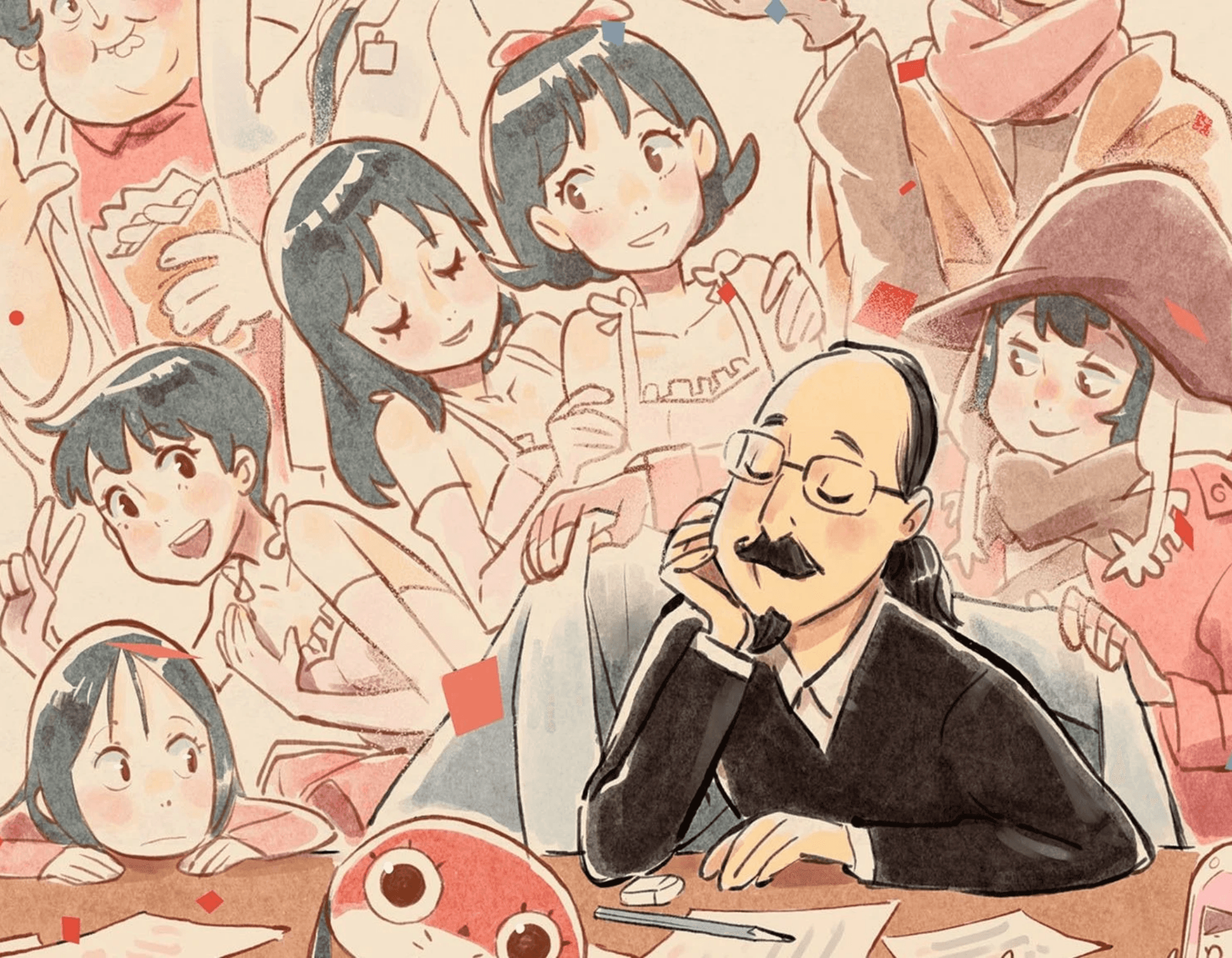

The Dreamscapes of Kon Satoshi

Few could be compared with Kon Satoshi (1963-2010), who leaves such an indelible impact on the [...]

Few could be compared with Kon Satoshi (1963-2010), who leaves such an indelible impact on the art of cinema with only four feature films and an animated series under his belt – less is more comes to define the genius of the visionary Japanese director, who died of pancreatic cancer in 2010 at the age of 46. In addition to the influence of his films on Japanese animators who came after him, traces of Kon’s creative impact can be seen in Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream (2000) and Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010), among others.

Citing science fiction as his favourite genre, Kon’s films go beyond pure imaginative and futuristic reverie, excelling at exploring the blurred lines between reality and fantasy as well as the public and the private. Kon recognised that nothing is more terrifying than actions that stem from a person’s anxieties and insecurities, making them the root of the horrors in his films. Perfect Blue (1997) delves into the psychological toll of physical and mental violence on a pop idolturned- actress; Paranoia Agent (2004) shows the ripple effect that a single act of violence can have on a community; Paprika (2006) depicts traumas and fears manifesting in dreams.

Though constrained by relatively low budgets, Kon’s films that brimmed with imagination and artistry have proven that creativity knows no bounds. In whimsical flights of imagery that obfuscate the real and the unreal of cinema, Millennium Actress (2001) took full advantage of ways that animation could subvert traditional storytelling; while in stunning yet dizzying visuals, Tokyo Godfathers (2003) delivers a twist-filled Christmas fable that finds magic in a cruel and sometimes violent reality. Kon unremittingly subverted expectations and broke through genre constraints, making him an inimitable genius of his craft. Through this retrospective, and Pascal-Alex Vincent’s documentary Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist (p.10), in remembrance of the 10th anniversary of his untimely passing, fans can revisit his timeless classics and his spirit of perfectionism.

From Darkness, Kim Ki-duk

A true-to-the-core creator whose cinematic violence raises awareness for society’s underbelly, or a rotten-at-the-heart exploiter who directs [...]

A true-to-the-core creator whose cinematic violence raises awareness for society’s underbelly, or a rotten-at-the-heart exploiter who directs with abuse? Kim Ki-duk (1960-2020) is no doubt a controversial figure both for his films and personal life – he is the only South Korean director to have won top prizes at Cannes, Venice and Berlin film festivals; yet he remains a despicable son of his mother country, living in self-exile after being accused of sexual misconduct, and died of Covid-19 in Latvia last year.

Beyond dispute, Kim made his name as a champion of the Korean New Wave with a series of violent yet aesthetically challenging features. His directorial debut, Crocodile (1996), heralded the arrival of a self-taught maverick, who caught international sensation with his shocking yet beautifully crafted dramas. Not for the faint of heart, nor mind, his films are morbid and deliberately antagonistic towards the audience – some regard them as highly accomplished works of art, unflinchingly depicting poverty and brutality that spark important debates in society; others criticise his extreme human cruelty and cinematic assaults on women for being perverted, misogynistic and sadistic.

From the libidinous The Isle (2000), the Buddhist transcendent Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (2003), to the visceral and morally complex Pieta (2012), Kim’s films cohere into a compelling body of work permeated with religious iconography, psychosexual characterisations and sociocultural allegory. Conceiving a world sometimes circumscribed by water, and sometimes engulfed by darkness, the auteur used his camera to reveal anger and agony, expressing brutal love and solitude in sensational imagery and haunting narratives with a vision grounded in sin and redemption – for those who believe in it.

“I try to discover a good scent by digging into a garbage heap,” Kim once said of his approach to filmmaking. Whether it is the scent of heaven or the stink of hell, it’s for you to decide.

DCP of Crocodile and 35mm prints of Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring , Samaritan Girl , The Bow courtesy of the Korean Film Archive

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)