Programme

Brian De Palma, the Obsessive Cineaste

The documentary De Palma (2015) begins with the director recalling going to see Alfred Hitchcock’s dark masterpiece Vertigo (1958) for the first time at Radio City Music Hall in New York, and the indelible impression it made on him. “I will never forget it,” he says. What’s so compelling about Vertigo, De Palma explains, is that Hitchcock is “making a movie about what a director does, which is basically create these romantic illusions and makes you fall in love with it and then kills it – twice. And it’s what we do as directors. We create these beautiful women, these exciting virile men, we get audiences involved in their stories and emotionally attached to them. …It is something that has fascinated me since I saw Vertigo.” That fascination has deeply influenced De Palma since he began his film career in the 1960s.

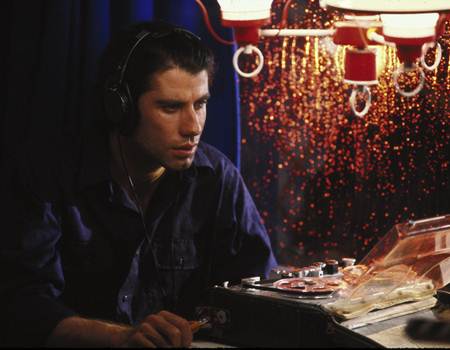

Born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1940, De Palma has enjoyed a career as wildly diverse as any of his contemporaries that emerged in the New Hollywood wave of the 1970s. The studio system had collapsed; the Hayes Code, which had set moral guidelines for movies since the 1930s, was outdated and ultimately discarded; and American values were quickly changing in the era’s counter-culture movement. With Hitchcockian films such as Obsession (1976), Dressed to Kill (1980) and Body Double (1984), De Palma became known for his homages to the Master of Suspense, but his filmography reveals other important genres: horror, most notably in the classic Carrie (1976); violent gangster dramas, including Scarface (1983), The Untouchables (1987) and Carlito’s Way (1993); and his big-budget blockbusters – Mission: Impossible (1996), which struck box-office gold, and Mission to Mars (2000), a huge financial flop.

But whichever genre De Palma chooses to work in, there is a consistency to his style: the tracking shots, the split screens, the explicit manipulation of audiences’ emotions. Responses to his films over the years include high praise from noted American film critic Pauline Kael (she describes De Palma as an artist) to outrage from advocacy groups that perceive some of his films as glorified violence against women. But De Palma remains as a film student’s treasure. “I love to make movies that are basically created on pure cinematic ideas,” he notes in the documentary. And his romance with Hollywood has been as passionate and contemptuous as any great love affair. “The Hollywood system we work in – it does nothing but destroy you,” De Palma says. “There’s nothing good about it in terms of creativity.” And yet he continues to carry on.