2019

Eric Rohmer: Six Moral Tales

“Why film a story when one can write it? Why write it when one is going to film it?” This is how Eric Rohmer (1920-2010) introduced his Six Moral Tales. Starting from his debut feature The Sign of Leo (1962), his conception of cinema – a profound taste for lively narratives that built on the ambivalent qualities of the cinematic image – fully realizes the form of these tales on the screen, cementing his reputation as a master of world cinema.

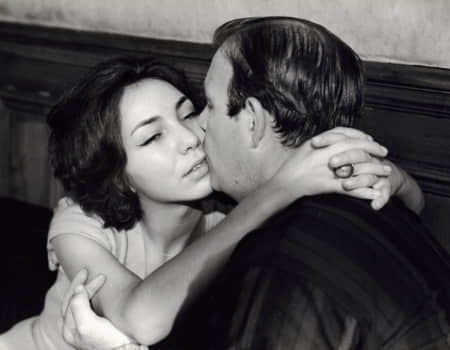

The progression of the Six Moral Tales reflects an evolution from adolescent to adulthood. The young men’s focus on self-interest and preoccupation with pleasure – deserting the bakery girl, belittling Suzanne and loathing the sexually-threatening Haydée in the three first films, gradually give way to self-restraint of desires and concern for moral life – resisting the temptation in My Night at Maud’s (1969), the perversity of desire in Claire’s Knee (1970) and the aggressive seduction in Chloe in the Afternoon (1972). This trajectory resonates with Rohmer’s shifting perspectives about fidelity, romantic arbitration and self-delusion.

Despite the casual naturalism and delicious sense of ambiguity, nothing was ever arbitrary in a Rohmer film. Considered himself a “Hitchcockian filmmaker,” Rohmer’s structured plotting, refined camera movement and attention to detail are finest examples of craftsmanship and sensitivity. Themes of male voyeurism, desire and hypocrisy exploded through the literary concept of the “unreliable narrator” in his moral tales – difference in varying complexity between the hero’s point of view and the film’s perspective through which the audience judges the character – are iconic of his ironic comedies.

“One natural, the other human… one of desire and appetite, the other heroism and grace” – the enduring dynamics and tension between his men and women are transformed into discreetly and acutely observed slices of life. Like watching paint dry? Maybe, if only it could be so captivating and amusing.

In the Memory of Wong Ain-ling

Spring has barely passed when winter returns. It has been a year since Wong Ain-ling left us. What she had written about films, and researched on films remain vivid remembrances for a love of cinema forever fresh. We hope that this selection of ten films much cherished by Ain-ling will be a reunion of some of cinema’s finest gems, and her exquisite narratives on them.

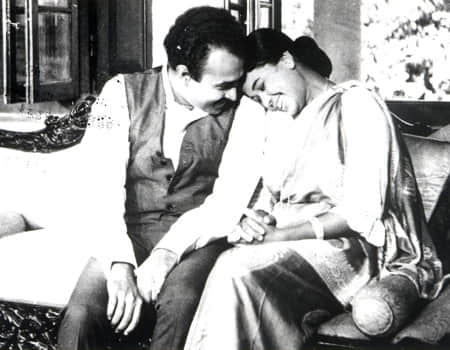

“The lights and shadows of cinema may be splendidly tempting. But none compares to this enigma of an orchid ever fragrant in my heart,” Ain-ling once wrote this about Spring in a Small Town (1948) in her book about the poet director Fei Mu.

Ain-ling’s words on films were every syllable as fragile and vulnerable as every frame of the films she was writing about: remember The Marquise of O (1976), Floating Weeds (1959), A Day in the Country (1936), and Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (1931).

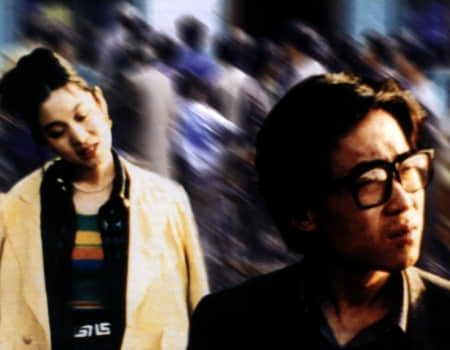

She had this eye for obscure works off the beaten track of mainstay arthouse cinema. Ain-ling paid tribute to Lester James Peries with a retrospective at the HKIFF decades before he was “rediscovered”. She admired Glory to Eternity (1943) for its courage to be, and shrewdly recognised Jia Zhangke’s talent way back when Xiao Wu debuted in 1997.

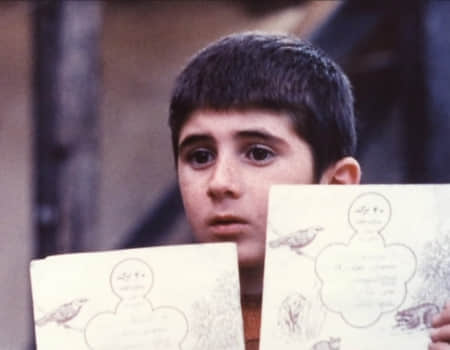

Her love of the quiet abundances of life resonated in her fondness for The House in the Woods (1971), and of course, Abbas Kiarostami’s works and the Iranian Cinema.

Ain-ling liked to compare cinema to dreams. May her lyrical words bring us once more into the sweet dreams of cinema.